The time factor

By: Robert Wagner

May 29, 2017

One of the most important considerations in analyzing risk is the choice of time-frame. Often, not enough thought is given to this choice, which tends to result in a default position: measure what appears easily measurable, which usually leads to a very short-term focus.

Sure enough, some of the bad things that can happen will happen suddenly. A lightning strike, a tornado, a car accident, or a collapsing building can take place in a short period of time. Similarly, markets also experience flash-crashes, sudden bankruptcies, scandals, and other short term shocks. In a business setting, however, most of the important risks tend to play out over much longer time periods. I am going to concentrate here on market risk, but I suspect the same concepts apply to many other types of risks as well.

Market risk refers to the potential change in the perceived value, or market price of a firm's various exposures (please see previous note on exposures). Buying and/or selling various types of assets with the objective of generating a profit often involves this type of risk. Some firms may actively choose to take market risk, while some actively look to reduce their risk by hedging, and many are involved with both of these activities. Quantitative risk analytics and metrics are relatively easy to deploy given the large amounts of pricing data available for most markets and traded instruments. Algorithms and analytical systems have become very good at crunching the data and producing estimates of potential risk, or variability in the firm's exposures.

In my experience, however, the resulting analysis is very short-term focused, too much so. Take for example Value-at-Risk, one of the widely used market risk metrics. The typical time frame of analysis is one day, which is sometimes extended to 3-5 days, but the longer we extend the time period, the weaker the assumptions behind the models and the looser the connections between models and reality (In a later note I will share my thoughts on the benefits and short-comings of Value-at-Risk).

For all but perhaps the most liquid and relatively small exposures, a one-day time period is a very narrow way to define risk. It is analogous to running through a forest while looking firmly at the ground one step ahead of us. Most likely sooner or later we would end up slamming into a tree. If we were to raise the focal point of our vision and try to look further ahead, maybe we would miss some smaller trees but we would be unlikely to run into a large tree or into a ravine.

Another analogy I like to use is that of driving a car. When we drive, we don't tend to look right in front of the car, rather, we tend to look further ahead, closer to our visible horizon. We must be aware of our immediate surroundings, but that is not where we focus. The faster we drive (or the more risk we take), the farther ahead we tend to be looking as we understand more things may jump in front of us and it takes much longer to come to a stop.

Some key factors influence the chance of an accident. The quality of the car (systems, processes, analytics), the talent, personality, and experience of the driver (the risk takers), road and weather conditions (the market environment and complexity of traded instruments), the traffic, the speed (perceived level of risk) and ability to stop (liquidity under a stress environment and effectiveness of limits) would all be helpful to examine. Unique combinations of these various factors could reasonably lead us to estimate a range of how far forward to look ahead in order to ensure we can identify dangers, and be able to stop in time.

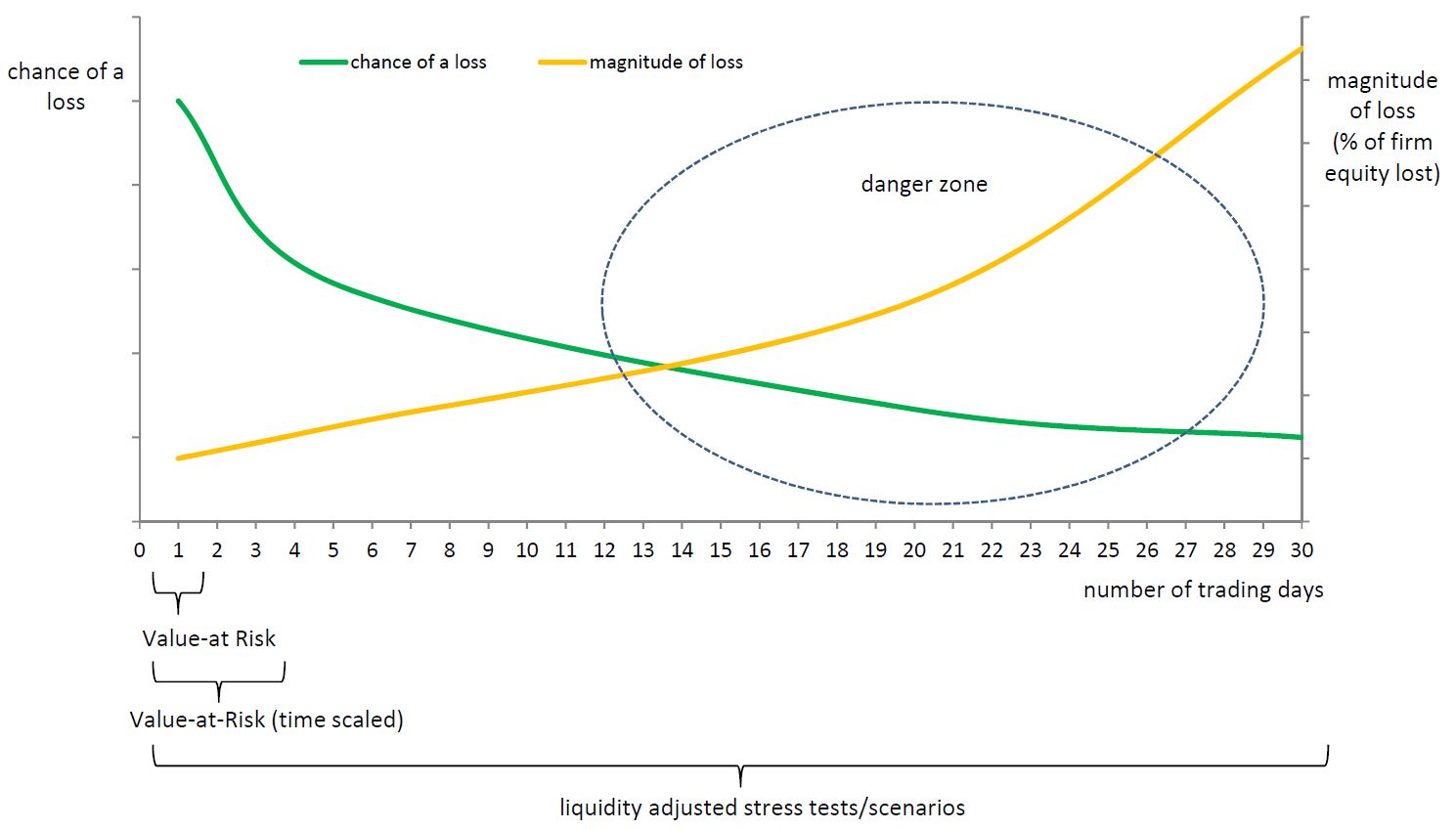

Flash-crashes only happen from time to time, whereas most important market movements take place over several weeks, months, or longer. The chart at the bottom of this note is an illustration of this point. Over the years I have experimented with various ways of drawing this chart. This is the best way I found so far to highlight the time factor simply.

The chart attempts to show the interaction of the time horizon, the probability of loss, and the expected magnitude of loss.

The green line shows the estimated chance of a loss. In the very short term, 1-3 days, Value-at-Risk or similar models are typically in use. Short term stress tests may also be used to complement the models, and explore extreme environments. The chance of this type of loss is relatively high (a 95% confidence VaR event is expected to happen on average one out of 20 days or roughly once a month). As we look at significant market movements over increasing time intervals, the corresponding probability tends to decline. As I mentioned the short-term scenario may depict a 5% probability on any given day, while the significant one month downside scenario is likely to carry a much lower probability (from the perspective of any particular day). An individual risk taker could potentially look at these scenarios (which may only happen every 3-5+ years) as too remote to worry about. However, a firm which intends to stay in business for a long period of time will likely experience a number of these extremes and must be able to weather the storm.

The orange line shows an estimated level of loss corresponding to the risk scenarios depicted by the green line. While experiencing a bad day may feel very rough, it is unlikely to represent a significant amount of firm capital. Experiencing a bad month or a couple of really bad months could be much more painful (the chance of a one-day "VaR event" is high, but the corresponding loss is relatively low... vs. the chance of a large 3-4 week event which is much more rare, but poses a significantly higher potential loss). In terms of focusing on what can cause real damage, risk should be analyzed and studied in the area labeled as the 'danger zone'. This zone may occupy different areas on the chart depending on particular strategies and the size of exposures. Some may be shorter term, while some, especially risks that are more strategic in nature may be best thought of in the context of many months or even years. Without a doubt, identifying these areas is as much art, gut feel and experience as it is a quantitative exercise.

One of the implications of the chart is the observation that market risks need to be studied with a longer time horizon in mind. Depending on the characteristics and size of exposures, the time frame and risk analysis needs to be appropriately adjusted. The other implication is that risk is sometimes significantly under-estimated. Firms that pay only attention to easily quantifiable, but often faulty short term metrics, may significantly under estimate what the actual risk is in their 'danger zone', the area of the chart that actually matters. Consequently, exposures may be allowed to build up to levels that under adverse scenarios can threaten the very existence of the firm.

In future notes I will explore ideas about how to correctly identify the 'danger zone' for significant exposures, and how to create the relevant analytics to understand risk, and provide a guide for the sizing decisions for those significant exposures.